Sometimes, within the design community, a strange debate surfaces: "Design is not art." It's surprising how regularly this argument comes up. The usual point is that art doesn't solve problems or carry functional weight, while design is all about tasks, goals, users, and business. But, in my view, a deep difference between design and art simply doesn't exist. Or, at least, it doesn't exist in the way it's usually described.

I'll approach this question from two angles. First, I believe that design is a form of art. This includes product design, interactive design, motion design, graphic design, and so on. Second, I am confident that art does solve problems. And it does so no less effectively than design.

When we contrast one with the other, we diminish both concepts. Design loses its depth of meaning and emotional resonance. Art loses its real practical impact. I want to show that this separation is a false dichotomy. It has no solid foundation.

Thesis 1

In art, the artist sets their task, while in design, someone else does

One common argument goes like this: in art, the artist formulates the task themselves, but in design, it's set by someone else. From this, they conclude that design is a mere craft that serves others, while art is free self-expression. But this is a rather weak distinction.

A designer can be an independent author and create a product based on their vision, without considering the market or audience. Or they can consciously abandon broad universality and create something for a narrow group of people. Conversely, try to appeal to everyone at once. This isn't a mistake, but a conscious strategy. Many indie designers work this way, creating utilities, apps, and websites for a community of like-minded individuals. And in this, they are no different from an artist who paints in their style and finds people who appreciate that style and are willing to pay for it.

Conversely, an artist can work based on a brief, paint portraits, illustrations, design books, or posters. This doesn't make them any less of an artist. What's important is not who sets the task, but how the person approaches it. How much effort is put into expressing something more than just meeting technical requirements. How much a personal perspective, a sense of form, time, and emotion can be felt in it.

Thesis 2

Art does not solve problems

Let's forget about the logic of conversions and retention for a moment and ask a simple question: why do people continue to create art, buy it, go to museums, hang paintings on walls, write music, and make films? The answer is simple: because it responds to specific internal and external needs. It solves problems: aesthetic, emotional, cultural, and social.

Art helps cope with anxiety, loneliness, gives a sense of beauty and meaning. It shapes perception, evokes feelings, raises important topics — from personal to political. It can point to a problem more accurately than analytics, faster than news, deeper than statistics. There are countless examples: Picasso's "Guernica," the works of Ai Weiwei, Rodchenko's posters, photographs from the Vietnam War. This is not just aesthetics. This is work aimed at specific goals: to attract attention, express protest, change opinion, create an effect.

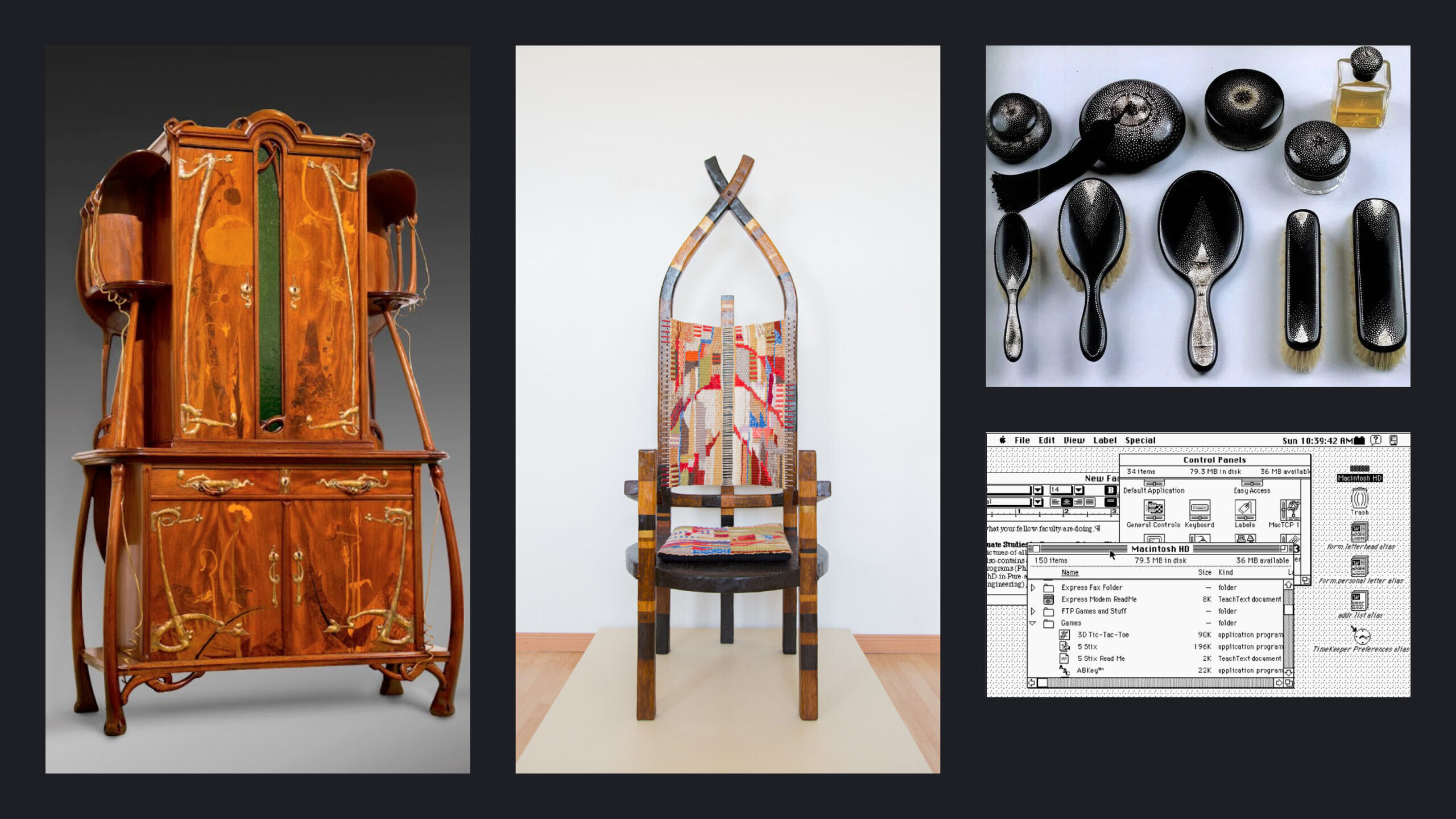

Incidentally, the same can be said about design. Many techniques we currently use in UI and UX came from art. The Bauhaus in the 20th century blurred the line between artist and engineer, and we continue along this path. A designer creates not just an interface, but also meaning and form. Their work influences the user's thinking, behavior, and mood. This is the connection with art, just with different tools and on a different scale.

Thesis 3

Art is about self-expression, while design is about the user

This argument is also heard often, but it's false. Of course, there are works created by artists only for themselves, "for the drawer," without considering the audience. But in most cases, art is directed at the viewer. It expects a dialogue. It wants to evoke an emotion, a reaction, a thought. Sometimes even provocation.

At the same time, design can also be subjective, authorial, not obligated to please everyone. If you go beyond purely applied design, you'll find that a large amount of design work is not done for the user. It's created for oneself, for research, for experiments.

By the way, I often recommend myself, when working on a task, to first imagine how I would want to solve it for myself. Without considering the brief. Without accounting for the "average user." This is something between curiosity and the egoism of self-expression. But that's where the power lies. It is precisely this approach that often gives birth to unique, vibrant solutions in which the author's personality is revealed.

Thesis 4

Art is timeless, while design becomes outdated

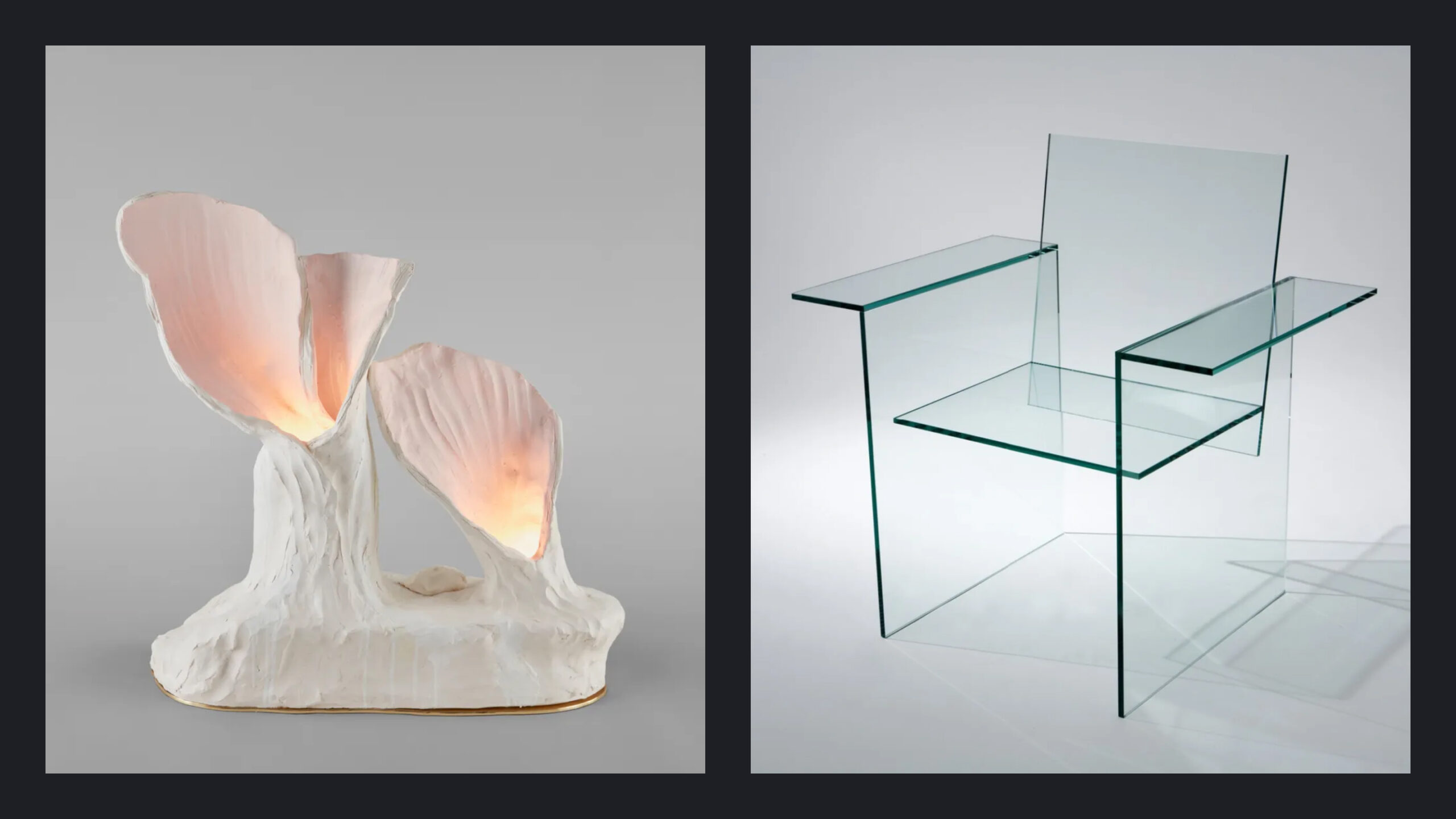

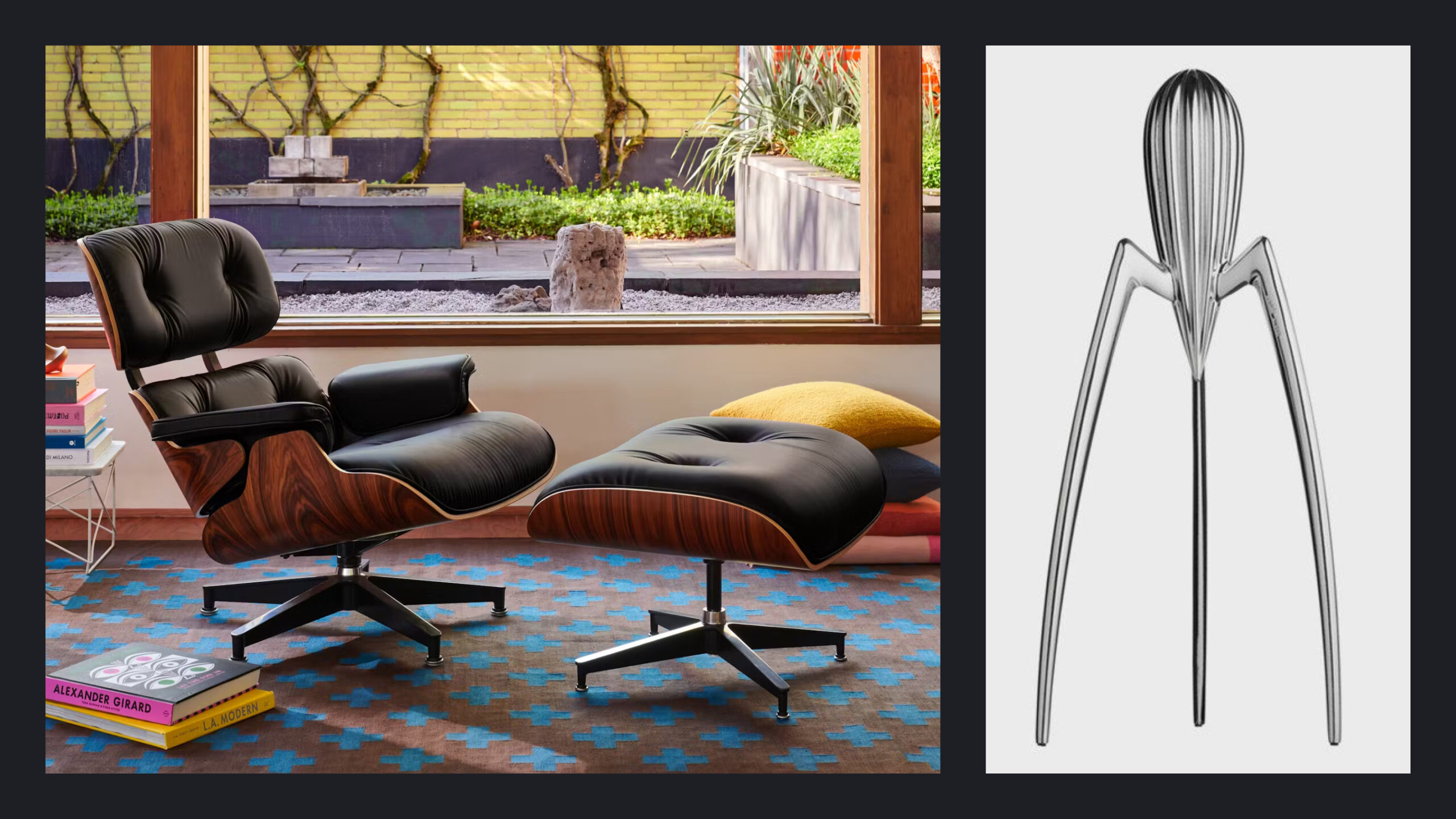

Sometimes people say that art is "for the ages," while design exists within the framework of trends, technologies, and the tasks of its time. This argument easily falls apart when we look at what is currently called art, and how many real products created with both functional and aesthetic value have turned into art. This includes classic typefaces, Bauhaus objects, Scandinavian chairs, and much more.

At the same time, a vast amount of art "dies" within the context of its era. A colossal number of artworks have been created in the last 100 years. However, we still remember and consider truly valuable only a small portion of them. I am sure that if you calculate it, this proportion is no more than 1% of all works that could claim "timelessness."

Conversely, many works of art intentionally engage with the current context, as a reaction to the here and now, as an attempt to draw attention to a social problem. Take the works of performance artists, for example. Of course, we will remember their actions, but as a historical fact, not as an act of art that we could observe in its original context.

Thesis 5

Art has no metrics, design does

This argument sounds like, "design can be measured, but art cannot, so they are fundamentally different." Let's be honest. Scientists still don't fully understand how the human brain works. Scientists still don't understand how and why certain decisions are made. Until we decipher how the brain works, many things in design cannot be measured: emotions, the "wow" effect, style, memorability, associations.

We can only measure the consequences of this influence in the form of conversions or other business metrics. But we cannot measure the influence itself, or why it has a certain effect, or whether it affects everyone the same way or differently.

It's the same with art. Many metrics assess the popularity or importance of an object after the fact: criticism, reaction, value, market, popularity. Especially in the modern world with likes, comments, auction values, and price lists for paintings on Wikipedia. Many things can be measured. But all these assessments are given as a societal reaction to art, not as an assessment of the influence of art on each viewer individually.

Thesis 6

Art creates value in itself, while design creates it through function

This thesis largely overlaps with Thesis 2. Here too, it all boils down to what we consider valuable.

In my opinion, value can take different forms. A thoughtful and meaningful film can change a person's life and views. Kind, well-chosen words can ease emotional suffering. A magnificent painting can carry aesthetic value. And well-executed design can carry both aesthetic and functional value.

Sometimes the aesthetic value of a design object is so great that we want to have it in our home solely because of that, not because of its functional part. At the same time, functional but soulless things bring us no pleasure.

It is said that in design, only solutions that can be tested and proven work. But practical experience shows that everything that truly has an impact doesn't always fit neatly into a funnel. An emotional interface is perceived as more convenient. Aesthetics build trust. Form is not decoration; it is the language through which a product speaks to a person. If design starts to lose its artistic quality, this language is also lost. Design becomes dead, grey, flat. It becomes just a utility. And nobody loves utilities; they are merely used.

Thesis 7

Design is about business

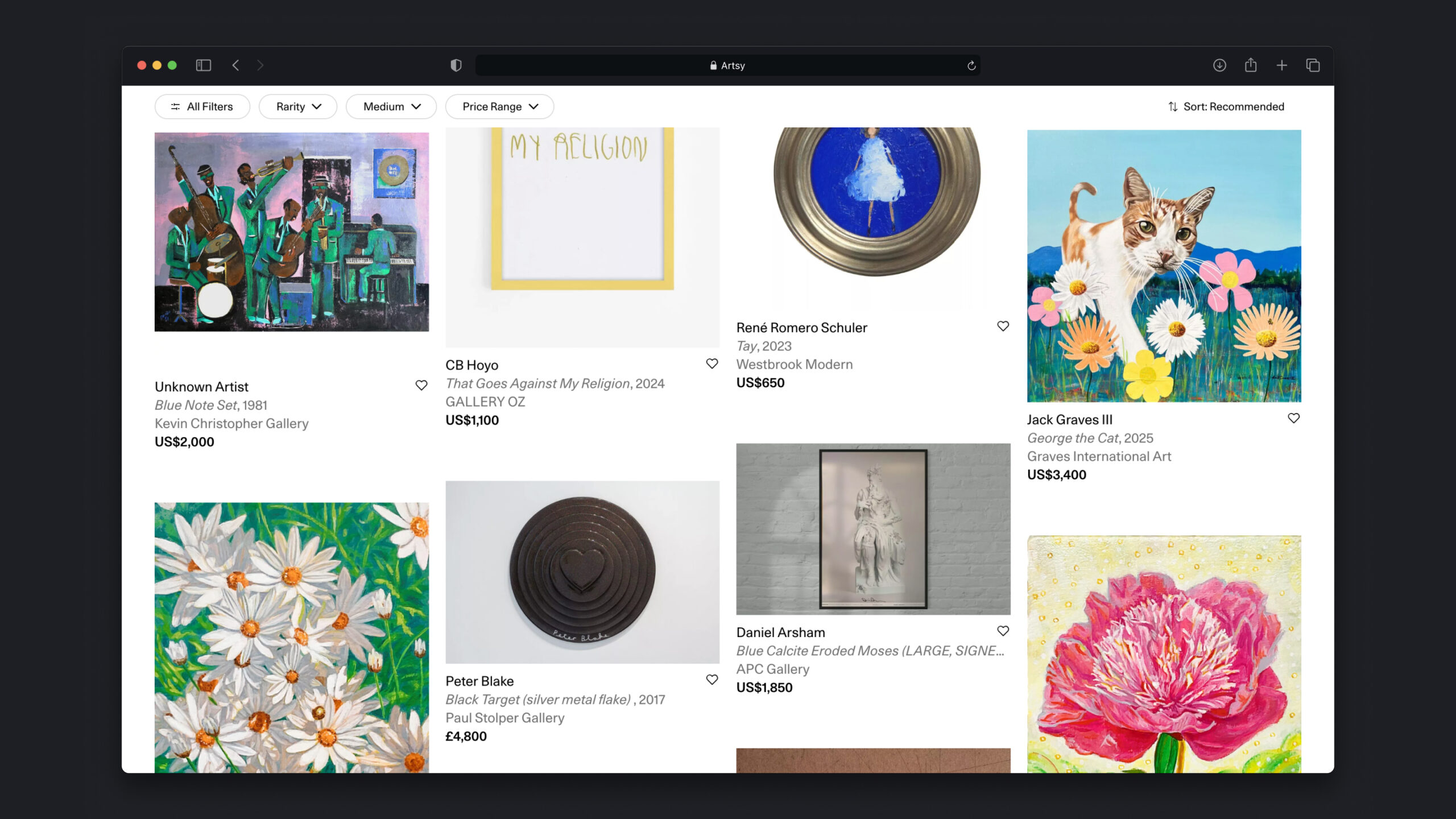

This is a trend. In some companies and teams, design, especially product UI/UX design, has indeed started to serve one purpose: to extract as much money as possible from users, including by using any available manipulations bordering on dark patterns. The very concepts of dark patterns are also becoming increasingly blurred.

I recently asked a colleague, a product manager, how many story points he would be willing to spend to achieve beauty. He replied — zero. Do we agree to such a future for design?

When we try to "sit at the table with business," we sacrifice emotionality, aesthetics, feelings. We are essentially saying, "Look, look! We — designers — are just like you! We are like the CEO, CPO, CTO, CMO, CRO, CFO! We are calculating, pragmatic, cold! We are about metrics, business, and money! We disregard beauty if it brings more cash! We ignore the user if the metrics go up!"

This looks pathetic. And it's a trap. The designer's strength lies precisely in being different, not in being similar. In empathy. In the ability to create something unique, convenient, expressive, emotional. Something that is not visible on charts but is felt. The strength lies in the ability to create balance within the team, to balance the corporate race for money with something more humanistic.

In fact, this last thesis, if allowed to develop, is truly capable of destroying design as a form of art. It can turn it into a dry set of psychological manipulations aimed at achieving business goals: FOMO, Scarcity, Hidden Costs, Confirmshaming, and even Social Proof, which has become quite innocent over the years.

People get tired of such design; they lose their receptiveness to it. In response to this fatigue, design becomes increasingly pushy, aggressive, and refined each year. Notification bells ring and shake more and more fiercely. Boxes and chests with "gifts" are thrust upon people more aggressively. We are increasingly moving away from being user advocates and creating aesthetic functionality.

Yes, I know I sound naive. I have been working as a product UI/UX designer for the last 14 years, and I understand everything. My last project was about nudging people towards a choice using Social Proof. This project helped business metrics. Yay.

Design is Art

Nevertheless, to summarize everything that has been said, I believe that art and design should not be contrasted. They should not be pushed to opposite poles. They are one and the same force of creative vision. We solve different problems, but the essence of these problems is the same. We are trying to respond meaningfully and beautifully to the challenge of society, the market, the inner world, or the technical environment. In this sense, design is art, albeit more utilitarian, more applied, and more scalable.

I think our task as designers is to remember this. Not to lose our artistic essence. Not to be afraid to say that we are also artists, that we create meaning, the beauty of forms, and emotions, that we have a voice. That we have the ability not just to "fix scenarios," but also to propose something new, expressive, and have an emotional impact. To be authors. Because as soon as we agree to the role of applied craftsmen, we lose a part of what makes it worth doing.

Drop me a line

skorobogatkonn@gmail.com